When the Sahara Was Green: The Forgotten Garden of Africa

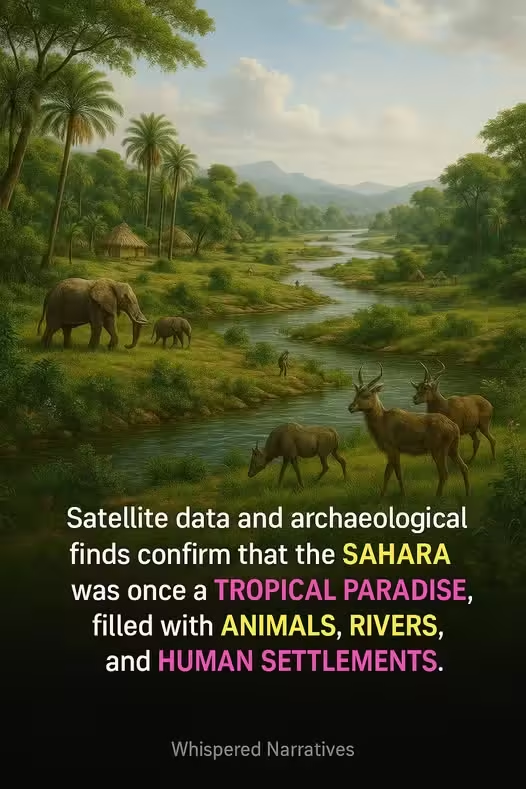

It’s nearly impossible to imagine today, but not long ago in geological time, the Sahara Desert—the vast, sun-scorched expanse we now associate with sand dunes, desolation, and extreme heat—was once a lush, green paradise. This surprising chapter in Earth’s climatic history is known as the African Humid Period, and it offers one of the most compelling stories of ecological transformation our planet has ever seen.

Spanning roughly 12,000 to 6,000 years ago, this period saw the Sahara region bloom into life, filled with grasslands, enormous freshwater lakes, and a thriving web of flora and fauna. Even hippos, crocodiles, and elephants once roamed the now-arid sands. Rivers flowed through what are now barren valleys, and early human civilizations flourished in an environment that looks nothing like the Sahara we know today.

What Caused the Green Sahara?

The Green Sahara was no accident. It was the direct result of changes in Earth’s orbital dynamics—specifically, a phenomenon known as Milankovitch cycles, which involve long-term variations in Earth’s tilt and orbit around the sun. Around 12,000 years ago, Earth’s axial tilt increased, intensifying the summer monsoon season across North Africa.

This shift caused the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ)—a region near the equator where trade winds converge and create rainfall—to move northward, bringing moisture-laden air over the Sahara. As a result, rain began to fall regularly over a region that had long been dry. What followed was nothing short of miraculous: the desert was transformed into savannahs, grasslands, wetlands, and vast lakes.

One of the most remarkable features of this period was Lake Mega-Chad, which at its peak covered an area larger than the present-day Caspian Sea—making it one of the largest freshwater bodies in Earth’s history. Rivers flowed into this giant lake, creating a thriving aquatic ecosystem that supported fish, birds, and large mammals.

Life in a Greener Sahara

With abundant water came an explosion of life. The Sahara during the African Humid Period teemed with wildlife that today can only be found in the tropical rainforests or savannas far to the south. Hippopotamuses wallowed in the lakes, giraffes grazed in open fields, crocodiles cruised along rivers, and elephants wandered through the grasslands.

This green paradise also became a haven for early human societies. Archeological evidence points to thriving settlements, complete with tools, pottery, and evidence of fishing and farming. People didn’t just survive here—they flourished.

We know this not only through fossils and excavations but also through ancient rock art left behind on cave walls and rock faces. In places like the Tassili n’Ajjer plateau in Algeria, stunning petroglyphs and paintings depict life in a lush Sahara: boats gliding through water, people herding cattle, wild animals hunting or drinking from rivers. These images are not myth—they are vivid records of a world that once was.

The Sudden Shift Back to Desert

But the greening of the Sahara was not permanent. Around 6,000 years ago, Earth’s orbit shifted once more, reducing the intensity of summer monsoons. As rainfall declined, the lakes began to dry, rivers slowed to a trickle, and vegetation gradually disappeared. Within a relatively short span of time—perhaps just a few centuries—the region underwent one of the most dramatic ecological reversals in Earth’s history.

The process wasn’t just environmental; it was societal too. As water sources vanished, human communities were forced to migrate in search of more hospitable conditions. Many of these populations likely moved toward the Nile Valley, contributing to the development of one of the world’s greatest civilizations—Ancient Egypt. In this way, the drying of the Sahara indirectly helped shape human history.

Today, only the faintest echoes of the Green Sahara remain. Subsurface imaging has revealed ancient riverbeds hidden beneath the dunes. Satellite imagery shows the outlines of dry lake basins and fossilized shorelines. Occasionally, archeologists uncover tools or bones that hint at a world lost to time and climate.

Why It Matters Today

The story of the Green Sahara isn’t just a fascinating footnote in Earth’s past—it’s a powerful reminder of how dynamic and sensitive our planet’s climate is. In just a few thousand years, a region larger than the continental United States swung from lush to barren and back again.

Understanding the African Humid Period also helps scientists model future climate scenarios. It shows us that climate change can be abrupt, dramatic, and capable of reshaping ecosystems and human societies in very short time frames. And it challenges the misconception that deserts are static, unchanging environments.

It also raises important questions: Could the Sahara ever be green again? Some scientists believe that with the right changes in orbital cycles—and perhaps under the influence of human-induced climate change—parts of the Sahara could once again become habitable. Already, there are fringe efforts exploring how large-scale ecological engineering (such as afforestation or irrigation) might reclaim parts of the desert for agriculture or habitation.

Conclusion: A Desert with a Hidden History

Today, the Sahara stretches over 3.6 million square miles, a sea of sand and stone under a blazing sun. It’s a place that feels eternal in its dryness. But beneath the surface lies a very different story—a story of rain, life, and transformation.

The African Humid Period reminds us that even the most extreme landscapes can—and have—changed. It speaks to the power of natural cycles and the delicate balance that governs our planet’s ecosystems. And it encourages us to look beyond the surface of the world around us, to imagine what once was, and to consider what might be again.

So next time you see a photograph of the endless Saharan dunes or read about a sandstorm sweeping across North Africa, remember: this was once a land of rivers and lakes, elephants and hippos, people and art. The desert keeps its secrets well—but not completely. You just have to know where, and how, to look.