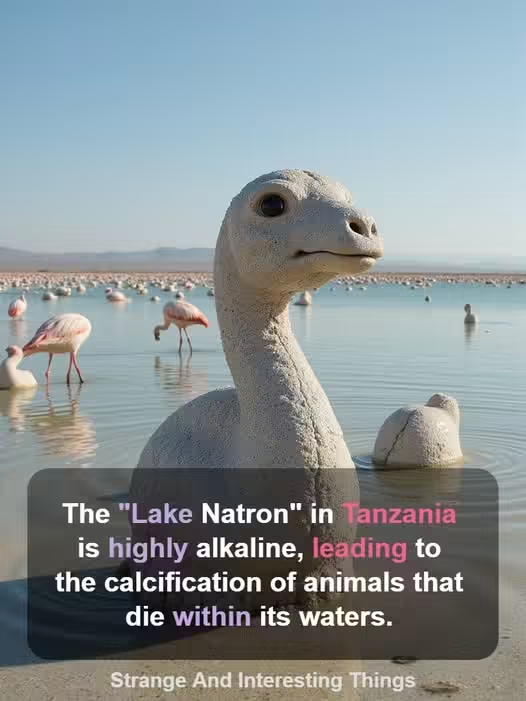

Lake Natron: The Petrifying Waters That Turn Life to Stone

In northern Tanzania, nestled near the border with Kenya, lies one of Earth’s most hauntingly beautiful and biologically bizarre landscapes—Lake Natron. This otherworldly body of water isn’t known for its serenity or recreation. Instead, it’s infamous for something far more macabre: it has the uncanny ability to preserve the dead, turning birds and other creatures into ghostly statues.

What makes Lake Natron so unique, and why does it seem to “petrify” life?

The Chemistry of Death: What’s in the Water?

Lake Natron’s name is derived from a naturally occurring compound—natron, a blend primarily composed of sodium carbonate decahydrate, along with baking soda (sodium bicarbonate). This mineral mix, abundant in volcanic regions, was once used by ancient Egyptians during the mummification process. And in Lake Natron, nature performs a similar ritual entirely on its own.

With a pH level that can reach as high as 10.5, the lake’s water is extremely alkaline, making it inhospitable to most living organisms. The temperature can soar above 60°C (140°F) during the hottest parts of the day, and the saline content can be so dense that it borders on caustic. In essence, Lake Natron is not just salty—it’s chemically aggressive.

Any animal that falls into the lake—whether from misjudgment, exhaustion, or misadventure—is likely to meet a chilling fate. The alkaline water rapidly calcifies their body, coating it in a rigid shell of salts and minerals. In some cases, it preserves their features so well that their final expressions appear frozen in time.

The Myth of Instant Mummification

Though often described as turning animals to stone “instantly,” the process isn’t immediate. When a bird or bat dies and ends up in the lake, the intense alkalinity gradually desiccates the tissues and hardens the corpse over time. The resulting figures are unsettling in their detail—eyes wide open, feathers intact, limbs stiff, all encased in a salty shell that mimics the texture of stone.

Famed wildlife photographer Nick Brandt documented many of these remains in a now-viral photo series. His stark images captured calcified birds perched upright or clinging to dead branches, as though they were still alive. The imagery sparked both fascination and horror, giving rise to the myth that Lake Natron “freezes” its victims like some mythical Medusa’s gaze.

Not All Is Death: The Flamingo Paradox

Despite its hostile nature, Lake Natron is paradoxically a cradle of life—at least for a few very special species. It’s the primary breeding ground for the lesser flamingo, a species found only in parts of Africa and India. Flamingos thrive in places others can’t tolerate, and Lake Natron is the perfect example.

How do they survive in such an inhospitable place?

Their diet is part of the secret. The lake supports a dense population of cyanobacteria and salt-loving algae, which bloom in vivid reds and oranges during the dry season. These microorganisms not only color the lake’s waters but also serve as the flamingos’ primary food source. In turn, the flamingos’ bright pink coloration stems from the pigments in the algae—an adaptation rooted in evolutionary chemistry.

Flamingos also benefit from Lake Natron’s isolation. The lake’s harsh environment deters most predators, providing a relatively safe breeding haven for the birds. During nesting season, tens of thousands of flamingos gather here, painting the shoreline in a surreal blur of pink against the lake’s metallic sheen.

A Volcanic Legacy

Lake Natron’s chemistry is largely influenced by its geographical surroundings. It sits in the East African Rift, a region shaped by tectonic activity. Nearby is Ol Doinyo Lengai, an active volcano revered by the Maasai as the “Mountain of God.” This volcano is unique in its own right—it erupts carbonatite lava, which is cooler and more alkaline than the typical silicate lava found elsewhere.

Over centuries, eruptions and mineral runoff from Ol Doinyo Lengai have fed Lake Natron’s chemical cauldron, contributing to its extreme pH and salinity. Rainfall is scarce, and high evaporation rates mean that minerals are continually concentrated in the lake basin. Essentially, Lake Natron is a giant, open-air chemical experiment—constantly shifting, always hostile, and utterly mesmerizing.

Conservation Challenges

Ironically, this desolate and dangerous environment is now under threat—from human activity. Plans have been proposed in the past to build hydroelectric dams or soda ash extraction plants near the lake, potentially altering the delicate balance that supports the flamingo breeding grounds.

Environmentalists have voiced concern that such developments could disrupt the ecosystem, affecting both the chemistry of the lake and the fragile populations that rely on it. The lesser flamingo, for instance, breeds almost exclusively at Lake Natron. A collapse of this habitat could push the species dangerously close to extinction.

For this reason, Lake Natron is not just a curiosity—it’s a conservation priority.

The Allure of the Unnatural

Why are we so captivated by places like Lake Natron?

Perhaps it’s the contradiction: a landscape so lifeless, yet teeming with specialized life. Or maybe it’s the lake’s ability to preserve, to create eerie sculptures out of once-living creatures. In a way, it’s a modern natural myth—where science, death, and visual poetry meet.

In a world of lush forests, vibrant coral reefs, and majestic mountains, Lake Natron reminds us that beauty can also lie in harshness. It forces us to confront our ideas about life and death, about decay and preservation. The lake doesn’t just kill—it transforms. And in that transformation, it leaves behind a legacy as haunting as it is unforgettable.

Final Thoughts

Lake Natron is a scientific marvel and an ecological paradox. While its waters calcify and preserve, they also sustain life in one of the most extreme niches on Earth. It’s a place where fire (volcanoes), salt (alkaline waters), and life (flamingos, algae) coexist in delicate balance.

Visiting Lake Natron isn’t for the faint of heart, nor is it your average eco-tourism destination. But for those who venture there, it offers a view into a world where nature writes its own strange and silent story—one statue at a time.